I was intrigued by the history of building codes and thought of doing some research on the issue. What unfolded was spectacular and I wanted to share it.

Building codes have been around for more than a few centuries. I think it is important to know the past as it gives clarity as to where we are heading. Allow me to walk you through time and explore how we reached the current building codes.

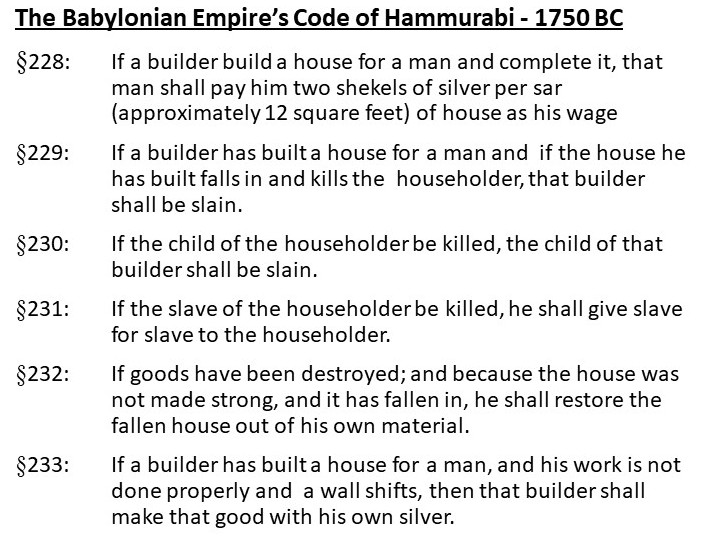

As early as 1750 B.C. …well 3768 years ago, the Babylonian Empire’s code of Hammurabi had numerous codes pertaining to buildings in general. Here are some codes which show the severity and seriousness of builders’ accountability.

Edict #228 talked about fair wage. “If a builder builds a house for a man and complete, that man shall pay him two shekels of silver per 12 square feet of house as his wage.”

Edicts # 229, 230, 231, 232, and 233 show the high accountability held by the builders. These penalties seem so absurd in today’s context… almost inhumane. These edicts are more like cold tit for tat rules. #229 says If the house falls and kills the owner, the builder shall face death penalty. For the loss of a child, goods, damage for shoddy construction, the builder would have to pay the same loss – the builder’s child would be killed if a child died due to the house falling down, the lost goods will be replaced, and the damage repaired at the builder’s cost. The onus on the builder was high. Unfortunately they did not have insurance. As builders and owners, our lives are much more secure and safe now. Professional and liability Insurance is our answer to any errors and omissions that we may commit. The severity of our actions has gone low, which has actually brought our standards as a society much lower. We have started to embrace mediocrity with pride… a topic for another time.

On 18th July 64 AD, Rome had the first great fire. It spread in the city fast and burned for five and a half days. Only four of the fourteen districts escaped the fire; three districts were completely destroyed and the other seven suffered serious damage. Subsequently, Rome was rebuilt, but this time in accordance with new principles of construction, sanitation and utility. Public and private construction was closely monitored throughout the remainder of the realm the Roman Empire.

In 1668, “London Building Act” was enacted by the parliament after the devastating fire of 1666 which destroyed thousands of buildings in London. New York city adopted its first building code in 1850. As a result of 1871 fire in Chicago, Chicago enacted its first building code and fire prevention ordinance in 1875. The NFPA, National Fire Protection Association, was founded in 1896 at which time it published its first sprinkler code.

In 1902, National Lumber Manufacturer’s Association was founded and they evolved bringing in codes and practices for the lumber industry since that time.

In 1922, The International Conference of Building Officials (ICBO) was founded. Five years later ICBO published the Uniform Building Code (UBC). Updated editions of the code were published approximately every three years thereafter until 1997. The 1997 code was the final version.

The UBC was replaced in 2000 by the new International Building Code (IBC), It was published by the International Code Council (ICC). The ICC was a merger of three predecessor organizations which published three different building codes as follows; International Council of Building Officials (ICBO): Uniform Building Code, Building Officials and Code Administrators (BOCA): The BOCA National Building Code; and Southern Building Code Congress International (SBCCI): Standard Building Code.

The first National Building Code of Canada (NBC) was published in 1941.

As Heraclitus of Ephesus who lived from 535 to 475 BC once said “The only constant is change”. This was profound. This has also been echoed by Buddha and many other philosophers later in time.

Subsequent editions of NBC were published in 1953, 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1977, 1980, 1985, 1990 and 1995.

The first National Fire Code of Canada was published in 1963; subsequent editions were published in 1975, 1977, 1980, 1985, 1990 and 1995. Every year the needs change.

In the late 90s, the energy crisis came and the Model National Energy Codes for Buildings and Houses were published in 1997.

The 1995 NBC split into nine parts;

Part 1 Scope and Definitions – provides the definitions and describes how the building code is applied;

Part 2 General Requirements;

Part 3 Fire Protection, Occupant Safety and Accessibility;

Part 4 Structural Design;

Part 5 Environmental Separation;

Part 6 Heating, Ventilating and Air-conditioning;

Part 7 Plumbing Services;

Part 8 Safety Measures at Construction and Demolition Sites;

Part 9 Housing and Small Buildings. This pertains to houses and certain other small buildings (less than 3 storeys high and 600 m2). Also called “Part 9 Buildings”. Part 9 drives the majority of the code requirements, with references to other parts where the scope of Part 9 is exceeded. Part 9 is very prescriptive and is intended to be able to be applied by contractors.

Larger buildings are considered “Part 3 Buildings” for which parts 1 through 8 apply. Part 3 is the largest and most complicated part of the building code. It is intended to be used by engineers and architects.

In 2012, Part 10 was added on to address the energy and water efficiency requirements.

The Building Code also references hundreds of other construction documents that are legally incorporated by reference and thus form part of the enforceable code. This includes many design, material testing, installation and commissioning documents that are produced by a number of private organizations. Most prominent among these documents are the Canadian Electrical Code; Underwriters Laboratories of Canada, a subsidiary of Underwriters Laboratories; documents on fire alarm design, and a number of National Fire Protection Association documents. ASHRAE – American Society of Heating and Refrigeration Engineers Standards are referenced and form part of the code.

A building code is a consensus document which regulates construction of buildings and is traditionally written by the NRCC (National Research Council Canada). The provinces adopts the code on the public’s behalf. Building code measures are public interest decisions and are designed to protect the public.

The building codes have historically been very prescriptive, but we are seeing a trend changing towards objective based codes. From the years 2006 to 2012, we saw a more evident shift from prescriptive to objective – a fundamental change from previous editions. An objective-based Code, as defined by National Research Council Canada (NRCC), includes objectives or goals that the Code is meant to achieve.

If a particular design does not meet the prescriptive requirements identified in the applicable Building Code, there is a provision to submit an alternative solution that meets the life safety and fire protection objectives of the Building Code. This is prepared under provision of the objective based Building Code, permiting the designers and engineers to achieve significant new innovative solutions while meeting the life safety and fire protection requirements of the applicable Code. Under the objective based Code system, all provisions of the Building Code are subject to a performance based review and submission of an alternative solution meeting the objective and intent of the Building Code. The alternate solutions must achieve at least the same level of performance and satisfy the same objective(s) assigned to the associated Code provisions.

The Building Code can be very basic and we must excercise some flexibility to achieve the innovative ways we build today. Understanding of the building codes and principles is paramount to design buildings we refer to as legacy.

There are myriad industry stakeholders invovled in establishing the building codes at all levels. Some city departments involved are: Planning & Development Services, Community Services, Fire Services, Sustainability Office, Facilities, Engineering Services, Legal Services, etc. And there are industry stakeholders such as Architectural and Professional Engineering Associations, Urban Development Institute, Canadian Home Builders Association, Greater Vancouver Home Builders, BOMA, Fenestration BC etc who all play vital roles in bringing the building industry perspective to the table. Last but not the least, there are various advisory committees which have their say in the development of codes and by-laws. To name a few, we have: Seniors Advisory Committee, Persons with Disabilities Advisory Committee, LGBTQ Advisory Committee, Women’s Advisory Committee.

A good example of involvement of a stakeholder is the introduction of unisex washrooms by the LGBTQ Advisory Committee. As our society evolves, the building codes evolve to address the changes presented.

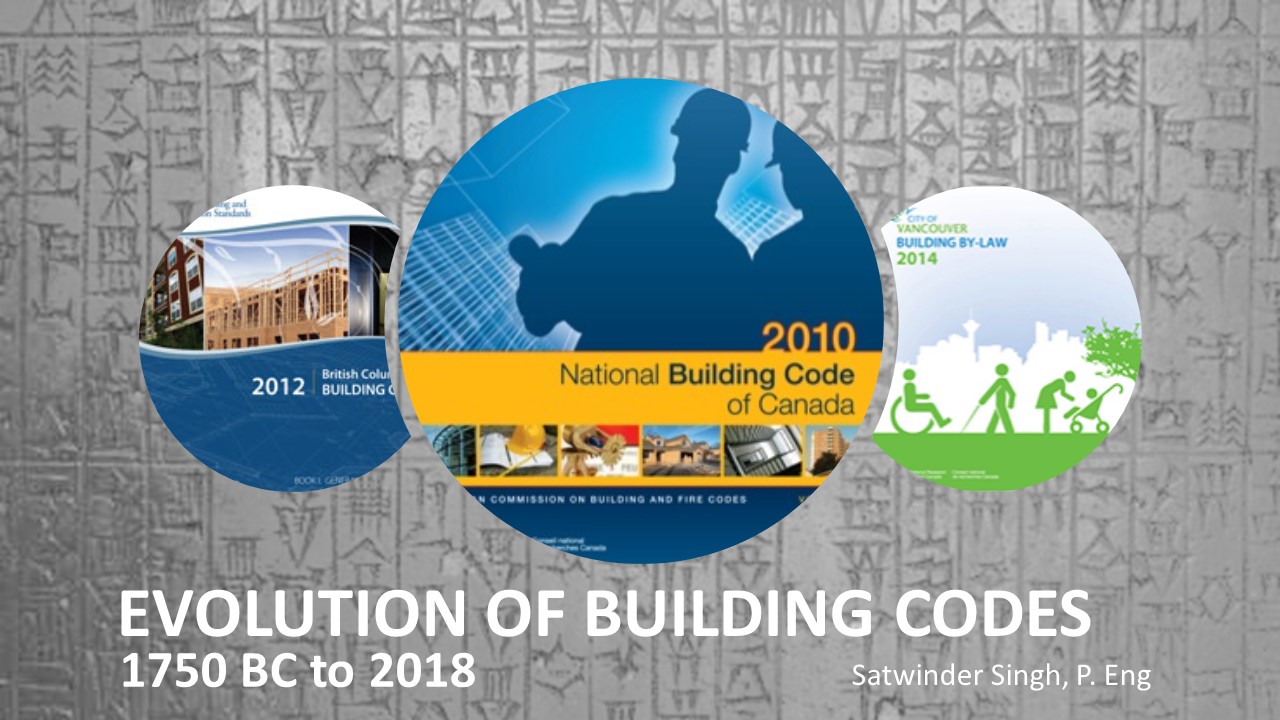

How are the local codes and by-laws enacted? It all starts with the National Building Code as a base code. It is better understood with the current code as an example.

2010 brought in the current National Building Code. Two years later, the British Columbia Building Code came into being – referred to as BCBC 2012. Basically, NBC was modified to suit unique requirements in the province of British Columbia. Subsequently two years after the City of Vancouver introduced its own by-law called the Vancouver Building By-law or VBBL 2014. Of course, all local municipalities have their own by-laws which go side by side the BCBC. Now – we have a new code coming in 2018, these will be based on NBC 2015. VBBL will most likely follow again in a couple of years after.

I hope this helps in understanding how the codes are evolving and how we have come to where we are today.

Satwinder – very cool!

The application below is due tomorrow (June 30, 2020); you should go for it!

Karen

From: National Research Council of Canada / Conseil national de recherches Canada

Sent: May-26-20 5:15 PM

To: Diane Meehan

Subject: Call for volunteers to serve on Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) / Bénévoles recherchés pour siéger aux comités permanents de la CCCBPI

Web Version

Call for volunteers to serve on Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC)

The five-year term for the current members of the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) will expire August 31, 2020. As a result, the CCBFC is issuing a call for volunteers to serve on the Commission for the development of the 2025 editions of the Codes. Anyone interested in participating is encouraged to submit their application via the Codes Canada website.

The CCBFC is an independent committee of volunteers established by NRC to develop and maintain the National Model Codes. The Commission oversees the work of nine standing committees that develop and improve the detailed technical content of the codes that helps protect the health and safety of Canadians. Commission members should have broad knowledge of the codes.

Commission members commit to a five-year term and may be re-appointed for further terms subject to maintaining a reasonable degree of membership rotation. The membership of the Commission has representation from the industrial and regulatory sectors, as well as general interest groups, and is balanced by geographic region.

Appointments do not carry remuneration; however, travel and hospitality expenses incurred in attending meetings are reimbursed by NRC. For more information, see CCBFC – standing committees on the Codes Canada website.

If you are interested in becoming a Commission member and participating in important National Code development work, please send an expression of interest to the CCBFC Secretary using the online form on the Codes Canada website before June 30, 2020. Please include a 120-word summary of your relevant experience and attach/append your resume.

For further information, please contact the CCBFC Secretary, at CCBFCSecretary-SecretaireCCCBPI@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Contact:

CONST Codes Inquiries

Email: CONSTCodeInquiries@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Bénévoles recherchés pour siéger aux comités permanents de la CCCBPI

Le mandat de cinq ans des membres actuels des comités permanents de la CCCBPI expirera le 31 août 2020. Par conséquent, la CCCBPI est à la recherche de bénévoles pour faire partie de ces comités techniques en vue du prochain cycle d’élaboration des codes. Toute personne intéressée à siéger à l’un des comités est invitée à soumettre sa candidature sur le site Web de Codes Canada.

La CCCBPI est un organe indépendant, formé de bénévoles, qui a été créé par le CNRC pour élaborer et mettre à jour les codes modèles nationaux. Elle supervise les travaux de neuf comités permanents et fait appel à l’expertise de membres œuvrant dans divers domaines techniques pour élaborer de meilleurs codes et ainsi contribuer à mieux protéger la santé et la sécurité des Canadiennes et des Canadiens.

Les membres des comités techniques sont nommés pour un mandat de cinq ans qui peut être reconduit, à condition de maintenir un degré raisonnable de rotation des membres. L’industrie, les organismes de réglementation et les groupes d’intérêt général sont représentés au sein des comités et les membres sont répartis de façon équitable par région géographique.

Le travail n’est pas rémunéré, mais le CNRC rembourse les frais de voyage et d’accueil engagés par les membres pour assister aux réunions. Pour en savoir plus, consultez la page CCCBPI – Comités permanents sur le site Web de Codes Canada.

Si participer aux importants travaux d’élaboration des codes nationaux vous intéresse, veuillez faire parvenir une déclaration d’intérêt, en précisant à quel(s) comité(s) permanent(s) vous désirez siéger, à la secrétaire de la CCCBPI en utilisant le formulaire en ligne fourni sur le site Web de Codes Canada d’ici le 30 juin 2020. Vous devez également joindre à votre candidature un texte d’au plus 120 mots résumant votre expérience pertinente, ainsi que votre curriculum vitae.

Pour plus de renseignements, veuillez communiquer

avec la secrétaire de la CCCBPI, à l’adresse CCBFCSecretary-SecretaireCCCBPI@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Renseignements :

Informations des codes

Courriel : CONSTCodeInquiries@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

National Research Council of Canada | Conseil national de recherches du Canada

1200 Montreal Rd. | Ottawa | Ontario | K1A 0R6

(613) 993 9101 | info@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Feedback form / Rétroaction

Subscribe | Unsubscribe | Abonnement | Désabonnement

From: National Research Council of Canada / Conseil national de recherches Canada

Sent: May-26-20 5:15 PM

To: Diane Meehan

Subject: Call for volunteers to serve on Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) / Bénévoles recherchés pour siéger aux comités permanents de la CCCBPI

Web Version

Call for volunteers to serve on Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC)

The five-year term for the current members of the Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes (CCBFC) will expire August 31, 2020. As a result, the CCBFC is issuing a call for volunteers to serve on the Commission for the development of the 2025 editions of the Codes. Anyone interested in participating is encouraged to submit their application via the Codes Canada website.

The CCBFC is an independent committee of volunteers established by NRC to develop and maintain the National Model Codes. The Commission oversees the work of nine standing committees that develop and improve the detailed technical content of the codes that helps protect the health and safety of Canadians. Commission members should have broad knowledge of the codes.

Commission members commit to a five-year term and may be re-appointed for further terms subject to maintaining a reasonable degree of membership rotation. The membership of the Commission has representation from the industrial and regulatory sectors, as well as general interest groups, and is balanced by geographic region.

Appointments do not carry remuneration; however, travel and hospitality expenses incurred in attending meetings are reimbursed by NRC. For more information, see CCBFC – standing committees on the Codes Canada website.

If you are interested in becoming a Commission member and participating in important National Code development work, please send an expression of interest to the CCBFC Secretary using the online form on the Codes Canada website before June 30, 2020. Please include a 120-word summary of your relevant experience and attach/append your resume.

For further information, please contact the CCBFC Secretary, at CCBFCSecretary-SecretaireCCCBPI@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Contact:

CONST Codes Inquiries

Email: CONSTCodeInquiries@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Bénévoles recherchés pour siéger aux comités permanents de la CCCBPI

Le mandat de cinq ans des membres actuels des comités permanents de la CCCBPI expirera le 31 août 2020. Par conséquent, la CCCBPI est à la recherche de bénévoles pour faire partie de ces comités techniques en vue du prochain cycle d’élaboration des codes. Toute personne intéressée à siéger à l’un des comités est invitée à soumettre sa candidature sur le site Web de Codes Canada.

La CCCBPI est un organe indépendant, formé de bénévoles, qui a été créé par le CNRC pour élaborer et mettre à jour les codes modèles nationaux. Elle supervise les travaux de neuf comités permanents et fait appel à l’expertise de membres œuvrant dans divers domaines techniques pour élaborer de meilleurs codes et ainsi contribuer à mieux protéger la santé et la sécurité des Canadiennes et des Canadiens.

Les membres des comités techniques sont nommés pour un mandat de cinq ans qui peut être reconduit, à condition de maintenir un degré raisonnable de rotation des membres. L’industrie, les organismes de réglementation et les groupes d’intérêt général sont représentés au sein des comités et les membres sont répartis de façon équitable par région géographique.

Le travail n’est pas rémunéré, mais le CNRC rembourse les frais de voyage et d’accueil engagés par les membres pour assister aux réunions. Pour en savoir plus, consultez la page CCCBPI – Comités permanents sur le site Web de Codes Canada.

Si participer aux importants travaux d’élaboration des codes nationaux vous intéresse, veuillez faire parvenir une déclaration d’intérêt, en précisant à quel(s) comité(s) permanent(s) vous désirez siéger, à la secrétaire de la CCCBPI en utilisant le formulaire en ligne fourni sur le site Web de Codes Canada d’ici le 30 juin 2020. Vous devez également joindre à votre candidature un texte d’au plus 120 mots résumant votre expérience pertinente, ainsi que votre curriculum vitae.

Pour plus de renseignements, veuillez communiquer

avec la secrétaire de la CCCBPI, à l’adresse CCBFCSecretary-SecretaireCCCBPI@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca.

Renseignements :

Informations des codes

Courriel : CONSTCodeInquiries@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

National Research Council of Canada | Conseil national de recherches du Canada

1200 Montreal Rd. | Ottawa | Ontario | K1A 0R6

(613) 993 9101 | info@nrc-cnrc.gc.ca

Feedback form / Rétroaction

Subscribe | Unsubscribe | Abonnement | Désabonnement

HI Karen,

Thanks for the comment. I did not see it until now and it is probably too late now. I do appreciate you giving me heads up.

Regards,

Satwinder